Management: Administration, Entrepreneurship, and Marketing 2

Atena Publisher, January 26, 2022. (In Portuguese).

DOI: 10.22533/at.ed.51622240117

ISBN: 978-65-5983-851-6

Human Resources in the Implementation of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM): impacts on organizational culture.

Authors: Álvaro Luiz da Silva Santos e Ewerton Emanuel Santos Silva

Capítulo 17, páginas: 212-222

This article addresses the role of the organizational psychologist and human resources in the implementation of the Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) methodology in industries, as organizational culture and employee well-being are directly affected by changes in process and people management. With the shift in organizational culture, it is necessary to monitor and understand how employees internalize the changes proposed by the implementation. The methodology of this study is basic, exploratory, qualitative, and conducted through a bibliographic research on the literature addressing the topic. The study contributes to the effective implementation of TPM in industries and to the subjective perspective of employees' needs, aligning productivity and process improvements with health prevention and promotion, thereby achieving the goal of bringing benefits to all involved.

INITIAL CONSIDERATIONS

The institutional dynamics is constantly referred to in the literature as something alive, seeking resources for survival, meeting its demands, and trying to alleviate the emerging negative impacts, with the main goal of longevity and continuous improvement.

Institutional environments are guided by complex interactions between people, forming basic assumptions about the valid way to behave. Individual and collective experiences define the way to deal with the challenges of the environment, starting from a successful experiment, receiving conscious and unconscious adherence from individuals, and being accepted by the group as the most appropriate (ZAGO, 2013).

Management methodologies also influence the work environment. One methodology that has been gaining more space in Brazil, especially in multinational industries, is Total Productive Maintenance (TPM), which modifies operational processes and the relationship between the employee and their workplace through methods that require greater autonomy in understanding their space, acting on improvement points, suggesting ideas, and redirecting solutions that increase productivity while reducing costs and losses in the production process (MELO; LOOS, 2017).

This complexity of connections between people and operational processes creates an interaction climate, which can be understood as the organizational culture. Organizational culture is, therefore, a set of habits and beliefs, established by norms, values, attitudes, and expectations by all members of the organization (CHIAVENATO, 2010).

The choice of the theme arises from the need to understand the role of human resources professionals and, above all, the organizational psychologist, in the face of TPM implementation in industries, recognizing the employee as one of the main actors to achieve the implementation goals and who, in this way, is impacted by it. The general objective was to describe TPM as a management approach and the role of human resources (HR) in the organizational change process, and the specific objectives focused on explaining the goals of the methodology, the role of the organizational psychologist in its implementation, and describing the possible impacts on organizational culture.

Thus, the development of this work provided a discussion of the TPM methodology not only for institutional benefits – which are present in most literature on the topic – but also addressed the impacts and benefits for an organizational culture that directly reflects on employees, being an extremely important theme for contributing to the well-being of people in their workplace, inherent to the studies of organizational psychology and HR professionals.

TOTAL PRODUCTIVE MAINTENANCE (TPM) AS A MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGY

Understanding business aspects and corporate methodologies is essential for Human Resources (HR) professionals who work within a strategic perspective and people management. A management methodology helps stabilize operations and guide guidelines for a series of company processes, controlling operations, allowing the identification of improvement points, causes, failures, and losses through a strategic analysis of the business and its applications (CROZATTI, 1998).

TPM originated in Japan in the 1970s, specifically in the Nippon Denso Co., part of the Toyota Group, as a set of activities focused on the company’s benefits, aiming to achieve maximum productivity effectiveness, improving Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE), maximizing the total life cycle of equipment, involving all departments and employees, from management to the shop floor, with the goal of zero losses[1] (MELO; LOOS, 2017).

[1] Zero loss is a term from Production Engineering that encompasses losses such as unnecessary operations or movements that generate costs and do not add value and, therefore, should be eliminated from the system, such as: waiting, transportation, storage, breakdowns, defects, overproduction, among other aspects (PERGHER et al., 2011).

In the 1970s and 1980s, Japan's economic progress and the expansion of automotive industries sparked the interest of companies in North America, Europe, Asia, and South America to adopt TPM techniques. In November 1991, the JIPM – Japan Institute of Plant Maintenance, holder of TPM worldwide, held the first Global TPM Congress in Tokyo, attended by over 700 people representing more than 100 companies from 22 different countries. This marked a global milestone for companies seeking to learn about and exchange ideas regarding the methodology, with participation from companies such as Alcoa, Ford, Kodak, Xerox, and Du Pont (ROBINSON; GINDER, 1995; CARRIJO; LIMA, 2008).

In Brazil, during the 1990s, multinational companies from various sectors applied for the JIPM TPM Awards, demonstrating the internalization of the methodology by these multinationals based in the country. Ribeiro (2010) highlights companies in 2008 such as Yamaha, General Motors, Alcoa, Stihl, Alumar, Texaco do Brasil, FIAT, Ford, Azaléia, Marcopolo, Multibras, Editora Abril, Votorantin, Eletronorte, Gessy Lever (now Unilever), Tilibra, Cervejaria Kaiser, Ambev, among others, as companies already operating with the TPM methodology and that had already won the JIPM award (CARRIJO; LIMA, 2008).

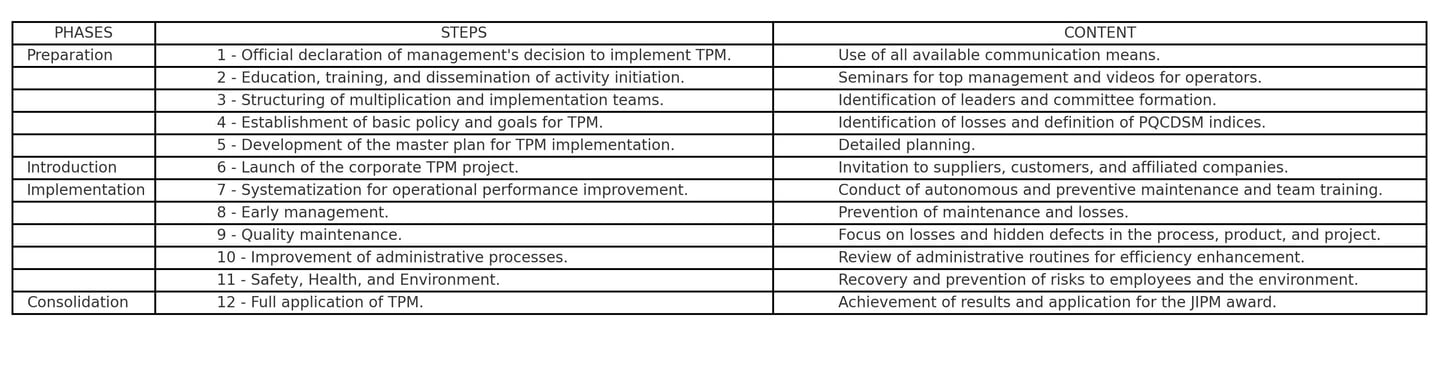

According to Carrijo (2008), the basis of TPM is made up of eight pillars that pave the way for the planning, organization, and monitoring of organizational practices. Together, they require applications and behavioral changes. The pillars address eight main topics: Autonomous Maintenance (AM), Specific Improvement (SI), Planned Maintenance (PM), Education and Training (ET), Safety and Environment (SHE), Initial Control (IC), Quality Maintenance (QM), and Administrative Areas (AA). According to Tavares (1999), the TPM implementation process follows four phases and 12 steps, as presented in Table 1 below.

As can be observed, indications of an intense organizational change are present in all phases of implementation, shaping both internal and external processes. The methodology's objectives and benefits must be clear to everyone, as the employee is the main actor in the construction and solidification of the methodology. Without their commitment and adaptation, it is impossible to progress through the phases and achieve efficiency at each stage of implementation.

It is essential to pay attention to the structural aspects inherent in the change process, understanding the time and space in which each productive area operates, its potentialities, and limitations. Training should be tailored to an approach in which the employee internalizes their responsibility for success, recognizing that the company's productive benefits will reflect on their professional career through new skills to be learned (KLOLOPANE et al., 2007).

This transformation directly affects the company's organizational culture, bringing impacts and benefits that must be closely monitored. Incorrect application as an imposition may lead to negative results, jeopardizing planning and triggering institutional problems beyond the TPM methodology.

IMPACTS AND BENEFITS OF TPM ON ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE

According to Moreira (2008), organizational culture carries core characteristics of a company’s or organization’s internal codes, describing attributes that can positively or negatively impact the company’s development or transformation. These attributes function as models of social representation, where each organization has its own objectives and experiences, constructs management models, adopts technologies, and shapes its members by seeking similarities between individual subjectivity and the organization, fostering skills, knowledge, values, and unique sentiments (ZAGO, 2013).

Chiavenato (2014) states that leaders play a crucial role in shaping and sustaining organizational culture through their decisions and actions. TPM changes organizational culture by introducing new tools and instruments into work processes, encouraging autonomy and productivity in various areas (MELO; LOOS, 2017).

Carrijo (2008) mentions several instruments used to achieve these goals, such as Tags, which signal equipment problems, hard-to-access areas, dirt points, accident risks, and other issues; Ideas, where employees identify improvement points in their production area and propose solutions; Step-by-Step Lessons (LPP), where employees share knowledge of area changes through concise, self-drawn explanations on paper; Skills Matrix, which discusses the knowledge required for each role, among other instruments.

Furthermore, other methodologies and tools can also be applied during TPM implementation, such as PM Analysis (Phenomenon, Physical, Mechanism); FMEA (Failure Mode and Effect Analysis); PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Action); SMED (Single Minute Exchange of Die); the 5 Whys method; and 6S (Seiri, Seiton, Seiso, Seiketsu, Shitsuke). These are common models in corporate and production environments that will increasingly be used on the factory floor, requiring greater critical thinking (RIBEIRO, 2010).

Sahu et al. (2017) indicate that applying these tools directly impacts people, as they require cognitive and emotional aspects such as autonomy, creativity, learning, adaptation, attention, and the development of new skills and various other competencies necessary for organizational change.

Carrijo (2008) notes that some employees may struggle to keep up with the new demands. The preparation phase is the ideal time to assess employees’ receptiveness to change. Pre-existing positive or negative feelings about work and the company may be intensified when their work environment changes due to new productivity mechanisms.

The new work dynamic will involve alignment meetings, new tools for performance indicator (KPI) tracking, and individual managerial expectations for TPM practice integration. This configuration may also require new job positions for internal or external employees dedicated to TPM practices (CARRIJO, 2008).

Employee profiles are also highly relevant to adaptability. Studies in administration and people management commonly emphasize that "companies value employees who are creative, flexible, and capable of adapting quickly to change" (OLIVEIRA, 2009, p. 65). A lack of such profiles within an organization can negatively affect implementation, especially considering the educational background of employees in operational and lower-complexity roles.

Regarding employee benefits, Nakajima (1989) highlights safe, pleasant, and productive workstations, improving relationships between people and equipment. This fosters a greater sense of well-being through continuous production flow and safety, reducing physical and emotional strain in daily operations and enhancing physical and psychological security.

Klolopane et al. (2007) emphasize that creating new job positions expands learning and skill development, promoting critical thinking and autonomy. This enables employees to move beyond their specific roles and integrate into other departments, opening opportunities for professional growth within or outside the company.

It is important to note that the tools used depend on the institution itself. Factors such as production processes, workforce size and education level, organizational structure, and training approaches can facilitate or hinder implementation. Understanding how employees perceive these changes depends on how the HR department approaches the transition (CONCEIÇÃO JUNIOR; SILVA, 2010).

The impacts and benefits of TPM on organizational culture are significant, and the implementation process directly influences the outcomes. The organizational psychologist plays a key role in preparing for implementation, as their ability to assess employees' subjective experiences, concerns, and challenges allows for a better approach to this new management methodology.

THE ROLE OF THE ORGANIZATIONAL PSYCHOLOGIST AS A STRATEGIC MEMBER OF HUMAN RESOURCES (HR)

Historically, HR has evolved from being merely an administrative and professional department, focused on managing daily routines such as payroll, legal bureaucracies, and other operational demands, to being recognized as a strategic participant in company management (BECKER; ULRICH; HUSELID, 2001).

In this context, organizational psychologists have also expanded their roles beyond recruitment, selection, and training, as traditionally studied in organizational psychology. Their work now includes activities related to quality of life, health, and well-being, acting as business partners in culture, job roles, and compensation, while remaining attentive to corporate responsibilities and societal demands (ZANELLI, 2002).

Thus, in the context of TPM implementation, the organizational psychologist, as a strategic HR member, should align their approach with the recommendations and objectives of the methodology set by JIPM, as well as case studies from other companies, particularly focusing on the Education and Training (ET) pillar. This involves integrating their professional ability to understand human subjectivity with the inherent changes of implementation.

JIPM recommends that the first step in the transformation process is conducting kick-off events for employees, symbolizing an initial milestone that marks a break from previous work patterns. The goal is to engage employees in understanding the established goals and gaining a better grasp of the program. A study conducted by Carrijo (2008) on four Brazilian industries showed that companies that did not conduct these events faced greater difficulties in internalizing the change process among employees and took longer to advance through the implementation phases.

In the same study, employees were asked about the aspects of success and failure during implementation. Factors contributing to success included commitment and participation from all employees, methodological rigor, communication, training, financial incentives, clarity of goals, transparency, professional development, recognition, and improved team and departmental cohesion. Conversely, failure points included lack of belief, complexity, lack of team involvement, resistance, production time constraints, lack of managerial accountability, absence of feedback, the need to understand how other companies operate, insufficient training, and a lack of deeper understanding of the methodology and its concepts (CARRIJO, 2008).

As previously mentioned, the entire process should center around employee inclusion as the focal point of change. The points outlined above should be considered and incorporated into kick-offs or development and training programs offered throughout the implementation process. The goal is to raise employee awareness of the professional and daily work benefits that the new organizational culture will bring.

Creative adaptation activities for TPM should be developed, tailoring the methodology’s specific activities to the company’s unique needs. Some companies have successfully implemented symbolic recognition strategies, such as giveaways (t-shirts, keychains, and other small items), which help distance the perception of increased performance pressure and responsibilities (CARRIJO, 2008).

It is necessary to monitor adaptation and address issues as they arise. According to Sahu et al. (2017), the failure of some employees to adapt may lead to their departure, requiring HR to assess whether the turnover rate aligns with the change and its business impact, particularly considering the self-development plan within ET. HR must emphasize that the program's goal is not to discard employees who struggle to adapt but to integrate TPM into the company’s existing culture and workforce.

The recruitment process for new employees should also be designed to ensure a cultural fit aligned with the new set of challenges. If necessary, adjustments to job roles and compensation structures should be considered. Onboarding can also serve as an adaptation strategy, introducing new employees to TPM methodology through mentors or facilitators who can help them meet goals and understand the objectives of each tool or instrument used within the company (DABADE; KULKARNI, 2013).

Once all stages and phases are completed, monitoring and adaptation remain continuous processes. Each new process or employee should undergo adaptation to the new organizational culture. Consolidation of these changes confirms the maturity of both teams and the company in facing challenges. Organizations certified with the JIPM award have demonstrated significant transformations in their work environments, achieving institutional and personal benefits, particularly regarding safety, professional growth, and workplace well-being (CARRIJO, 2008; DABADE; KULKARNI, 2013; SAHU et al., 2017).

In Brazil, consulting firms assist companies in structuring the necessary knowledge flow and creating transition rituals for the new culture. Companies that have sought such assistance, such as Pirelli, Lever, and Tetrapak, have successfully achieved JIPM certification. It is also recommended to visit other organizations already practicing TPM to support benchmarking efforts and gather insights from successful case studies to drive program development and overcome paradigm shifts regarding its implementation (CARRIJO, 2008).

HR should creatively adapt TPM tools to meet the needs of both the company and its employees. Planning is essential to align human dynamics with the transformation objectives proposed by the methodology. A differentiated approach to implementation will enable solid results, contributing to the sustainability and maintenance of TPM. It is through people that results are made possible.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The objective of this article was to describe TPM as a management methodology in industries and its impacts on organizational culture. It started from the historical process and its use by companies in Brazil and worldwide, presenting the stages and phases of implementation, instruments, and objectives, guiding how these processes could interfere with daily work and the role of HR and organizational psychologists in this scenario.

With the goal of increasing productivity and eliminating losses, TPM has been adopted by companies worldwide seeking competitiveness in their industries. This directly impacts the organizational context, affecting both the company’s culture and its employees. TPM methodology changes organizational culture by introducing new tools and instruments aimed at productivity into the work environment, requiring a reorganization of personnel in the execution of their tasks.

The organizational psychologist must remain attentive to these changes and seek solutions that aid in constructing an HR approach centered on people's subjectivity. This should be based on the awareness that employees are the primary agents of change and that the methodology brings benefits for both their personal and professional development. Implementation recommendations must be followed to avoid failure, as new attempts will be more challenging to reintroduce due to employees' potential loss of trust in the methodology.

Companies that currently apply TPM have observed significant results in various areas. The work environment has become more productive and enjoyable due to continuous production without machine stoppages or losses. Additionally, it has led to greater safety, the acquisition of new skills, professional growth, and enhanced physical and psychological well-being in the workplace.

Finally, it is essential to expand the discussion and conduct further theoretical-conceptual, methodological, and empirical research, particularly regarding the impact on employees. As the primary actors affected by the implementation, they play a crucial role in ensuring the methodology's success in achieving its objectives.

REFERENCES

BECKER, B. E.; ULRICH, D.; HUSELID, M. A. Gestão estratégica de pessoas com scorecard. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier Brasil, 2001.

CARRIJO, J. R. S. Adaptações do modelo de referência do Total Productive Maintenance para empresas brasileiras. Orientador: Carlos Roberto Camello Lima. 2008. 179 f. Tese (Doutorado em Engenharia de Produção) - Faculdade de Engenharia Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade Metodista de Piracicaba, Santa Bárbara do Oeste, 2008.

CARRIJO, J; LIMA, C. Disseminação TPM - Manutenção Produtiva Total nas indústrias brasileiras e no mundo: uma abordagem construtiva. In: Encontro Nacional de Engenharia de Produção, 28., 2008, Rio de Janeiro. Resumos [...]. Rio de Janeiro: ENEGEP, 2008. CHIAVENATO, I. Comportamento organizacional: a dinâmica do sucesso das organizações. 2. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier, 2010.

CHIAVENATO, I. Gestão de Pessoas: o novo papel dos recursos humanos nas organizações. 4. ed. Barueri, SP: Manole, 2014.

CONCEIÇÃO JUNIOR, J.; SILVA, S. Educação e treinamento como fator crítico para a Manutenção Autônoma (MA): Estudo de Caso de Implementação do Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) In: Encontro Nacional de Engenharia de Produção, 30., 2010, São Carlos. Resumos [...]. São Carlos: ENEGEP, 2010.

CROZATTI, J. Modelo de Gestão e Cultura Organizacional: Conceitos e Interações. Caderno de Estudos, São Paulo, v. 10, n. 18, p. 1-20, maio/ago. 1998.

DABADE, B. D.; KULKARNI, A. Investigation of Human Aspect in Total Productive Maintenance (TPM): Literature Review. IJERD, Maharashtra, v. 5, n. 10, p. 27-36, jan. 2013.

FONSECA, J. J. S. Metodologia da pesquisa científica. Fortaleza: UEC, 2002.

KLOLOPANE, P. et al. Some Effects of a Human Resources Strategy on Total Productive Manufacturing (TPM) improvement. IEEE. Oregon/USA: Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering & Technology, Portland, 2007. p. 2296-2304

MELO, F; LOOS, M. Análise da metodologia da Manutenção Produtiva Total (TPM): Estudo de caso. Revista Espacios, [S.l.], v. 39, n. 3, 2017.

MINAYO, M. Pesquisa social: teoria, método e criatividade. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, 1993.

MOREIRA, E. Clima Organizacional. Curitiba: IESDE Brasil S.A, 2008.

NAKAJIMA, S. Introdução ao TPM - Total Productive Maintenance. Tradução Mário Nishimura. São Paulo: IMC Internacional Sistemas Educativos, 1989.

OLIVEIRA, S. L. Sociologia das organizações: uma análise do homem e das empresas no ambiente. São Paulo: Cengage Learning, 2009.

PERGHER, I. et al. Discussão teórica sobre o conceito de perdas do Sistema Toyota de Produção. Gestão de Produção, São Carlos, v. 18, n. 4, p. 673-686, abr. 2011.

RIBEIRO, H. Desmistificando o TPM: como implantar o TPM em empresas fora do Japão. São Caetano do Sul: PDCA, 2010.

ROBINSON, C; GINDER, A. Implementing TPM: north american experience. Portland: Productivity Press, 1995.

SAHU, S. Total Productive Maintenance (TPM) Implementation – A Review. IJSRD, India, v. 4, n. 7, p. 254 – 259, abr. 2017.

TAVARES, L. Administração moderna da manutenção. Rio de Janeiro: Novo Pólo Publicações, 1999.

ZAGO, C. C. Cultura Organizacional: formação, conceito e constituição. Sistemas & Gestão, Niterói, v. 8, n. 2, p. 106 - 117, jun. 2013.

ZANELLI, J. C. O psicólogo nas organizações de trabalho. São Paulo: Artmed, 2002.